The only man I’ve ever wanted to marry is LeVar Burton. And yeah, for the obvious reason: He had all the books. At least, six-year-old me assumed those were all his books that they read on the show. He was the one recommending them before his army of adorable Outer Boroughs Children gave their picks, so you didn’t have to take his word for it, so clearly they were his, right?

As tiny tiny child, I organized my whole day around that half hour with Reading Rainbow. The show, its theme song, the little instrumental cue that preceded the kids with their book recs—those are probably the biggest Proustian madeleines I’ve got, and while it was my mom who taught me to read, my crush on LeVar certainly sped the process up. You can understand that I went into the Butterfly in the Sky with a certain amount of trepidation. What if it was… bad? What if, somehow, the documentary didn’t live up to the rush of emotions I have when I think about that show?

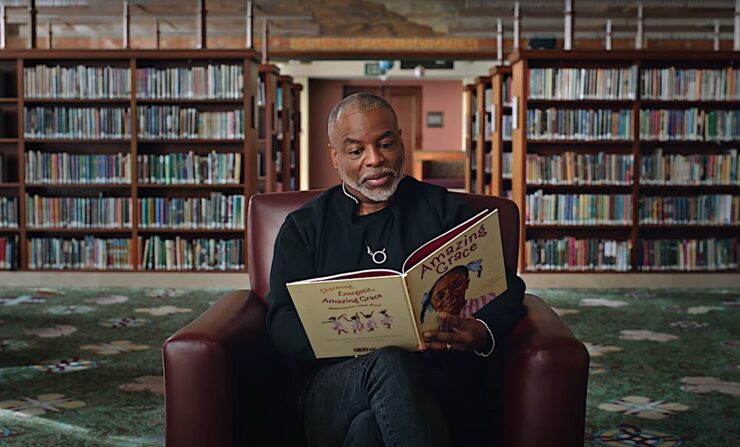

I’m so happy and relieved to say that if anything, it exceeded my expectations. Even when it upset me, it wasn’t the documentary that did it—it was learning about how rough things got at the end of the show’s run, as funding was cut, culture wars intensified, and Reading Rainbow was finally cancelled. But that’s also one of the film’s strengths: It really does tell the whole story of Reading Rainbow—the struggles to prove that kids would watch the show, the tug-of-war that occasionally happened over LeVar Burton’s fashion choices (Mr. Burton always, correctly, stood his ground), the way the show tried to incorporate heavy topics like mourning and racism into its runtime, the way it dealt with the aftermath of 9/11. And what comes through is that Burton and the producers, Twila Liggett, Cecily Truett Lancit, and Larry Lancit always operated from a place of respect for children’s intelligence. The other important thread is that this show wasn’t intended to teach children how to read, it was intended to help them love reading.

Reading Rainbow was a show for book nerds.

The documentary opens with a montage of those kids and their mini book reviews. We see the children as they were in the ‘80s and ‘90s (at my screening this was met with peals of affectionate laughter) with cuts to some of them as adults talking about their experience on the show. The filmmakers check in with them a few times and we get to hear about the adult lives they’ve created since their appearances. Butterfly in the Sky follows the usual documentary shape, where the filmmakers check in with producers and writers working through the development of the show, and cut between people with conflicting memories to gradually build the story of the show. This section culminates in LeVar Burton being hired (but I’ll come back to that in a second), shows us the plateau of the show’s success, and then gets a little elegiac as it talks about the show’s end. But unlike its most obvious pairing, Won’t You Be My Neighbor, Butterfly doesn’t have to end on a sigh for a lost era. It’s able to carry us into the future by giving space to the adult lives of those former book recommenders, to Jason Reynolds, a childhood fan who grew up to be a celebrated author (and the Library of Congress’ 2020-2022 National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature!), and to Mr. Burton and the show’s producers to talk about their lives after the show.

At one point we get an extended sequence of Steve Horelick, the composer of Reading Rainbow’s theme song, walking us through how he built the theme song. I can’t quite describe what this made me feel. That song is my Low, my “Warszawa”, the song that made me hear new possibilities in music before I even got to kindergarten—watching him recreate its genesis… okay, if Proust had choked on that madeleine? That’s how I felt for a minute there.

There’s also the usual fun reminiscences of adventures on location, trying to get footage in a cave full of bats (and their subsequent toxic guano), a shoot at an erupting volcano, the iconic set visit to Mr. Burton’s other gig, Star Trek: The Next Generation. The doc included the scene where the effect supervisor showed the kids at home how the “beaming up” effect was created, and I got to hear a theater full of adults “ooooh” in unison. Also: this is apparently the episode that most people bring up when they meet Mr. Burton, and indeed, it’s the one I brought up when I met Mr. Burton. He was very nice about it.

But let me talk about LeVar Burton for a moment. Again, the obvious comparison for Butterfly in the Sky is the (excellent) documentary about Fred Rogers, Won’t You Be My Neighbor?, which tells the straight-ahead story of how Mr. Rogers pioneered a new kind of television show for children—a slow, thoughtful show that treated children’s emotional lives with great seriousness, but which still, in a way, reinforced a certain kind of top-down structure. Mr. Rogers was an older man, in sensible clothes, talking directly into the camera as an adult speaking to children. He was an authority figure, and when he wanted to tap further into identification with children, he spoke through puppets. He was also a white man inviting kids into his respectable, neat, quiet suburban home. He’s the kind of person USian society has always told us is supposed to be in charge—as much as Mr. Rogers himself subverted that expectation by performing a different type of masculinity and adulthood than was usually seen on TV. Even so, Reading Rainbow is a different beast, and Butterfly in the Sky becomes strongest when it digs into that difference, especially the importance of LeVar Burton.

For the first seven-ish years of my life, I was in rural Pennsylvania. Extremely rural Pennsylvania, in the woods. I lived in a very white, very straight, very conformist world. While my own parents were always pretty iconoclastic, the world outside my house was full of rigid structures and mockery for anything “different” or “weird”. And literature, history, social studies—all of it was blindingly white. Moby white, Poe gazing at an ice shelf in Antarctica white.

Mr. Burton showed me a different world. A Black man with a gold hoop earring, who wore bright colors, not a suit (or even a fetching slacks-and-cardigan combo like Mr. Rogers), and who wore his facial hair in different ways in different episodes. A man who traveled all over the place, but who seemed to make his home in New York City, and was enthusiastic about the kind of hectic, LOUD life a person could live there. An adult who was enthusiastic and game to try anything—who interacted with the world like a kid, but like a kid who would want to go on an adventure with you, not mock you for being a freak. Now, obviously, I would never claim the level of identification that, for instance, Jason Reynolds does in his segments. I can’t know what it meant for Black kids to see Mr. Burton on TV in a landscape that was overwhelmingly white—I would imagine it was incredibly powerful, but I can’t tell those stories. I can say that he showed me a different road into adulthood. A version of adulthood that didn’t mean crushing myself down into what my society seemed to expect. He was an adult, but he wasn’t an elderly Mr. Rogers or one of the middle-aged-adult-ish-feeling humans of Sesame Street. He went to all-night diners, and midnight radio shows, and rooftop tar beaches. I could be him, to a certain extent, if I could just get to a city and trick people into thinking I was cool.

But again, one of the strengths of Butterfly is showing me the ways I couldn’t be him. The filmmakers remind us, again and again, that Mr. Burton became famous as the star of Roots. It reminds us that a lot of the arguments over his appearance were based in him being Black, and celebrating that, and not wanting to sand himself down for the white gaze. We’re shown footage of Mr. Burton on chat shows, talking about how his opportunities as an actor, even after the record-shattering success of Roots, were never up to par with those of his white peers. Again and again the filmmakers check in with Black fans of the show, people like Whoopi Goldberg (a co-producer on the doc, who was one of Mr. Burton’s co-stars on Next Gen) and Jason Reynolds, who speaks at length to the impact Mr. Burton had on him as a child.

It was thrilling to watch how often the filmmakers, and Mr. Burton himself, stressed these differences. Where Won’t You Be My Neighbor? was able to mostly paint a positive arc for Fred Rogers, with only the slight frustration at how the world has become louder, faster, more complicated, and how it would be better if we could all be more like Daniel Tiger (which, fair), Butterfly hammers home the idea that Reading Rainbow was made in the face of glaring prejudice from a society that hasn’t changed enough—because we haven’t changed it.

Because I’ve lived an in interesting life, and been far luckier than I understand (or deserve, if I’m being honest), I got to meet Mr. Burton at a literary event a few years ago. I managed to remain coherent, I didn’t propose we run away together, I didn’t cry. He held one of my hands in both of his, and looked me in the eyes, and told me that he was glad to meet me. He seemed to mean it? He seemed to be genuinely happy to meet the whole lot of us at the event, a roomful of competent professionals turned into heart-eyed children when he walked into the room. He talked about his mother, and how she taught him to read, and her passion for books and literacy and imagination. Since then, he’s started the LeVar Burton Book Club, the LeVar Burton Reads podcast (the fact that adults still want him to read to them is touched on in Butterfly), he judged a short story contest on this very website, and he recently hosted the National Book Awards and made a point of calling out some particularly irritating pro-censorship windbags to raucous applause.

He is still my hero, and still the only man I’d ever consider marrying. (I have my own books now, though, it’s cool.)

My theater filled with enthusiastic applause as the documentary ended, and I tried to take stock of the mood as I left. A group of people stayed in their seats talking excitedly about Butterfly and their own reading lives. A few people who didn’t seem to know each other coming in were now talking to each other. Two theater workers were standing in the doorway, having an impassioned conversation with a member of the audience about this movie’s distribution schedule. And as I left, the kids behind the counter—who were almost certainly not even born when Reading Rainbow went off the air—were singing the theme song.

Find out the story of how the actual feature book segments of Reading Rainbow were filmed with pioneering digital technology at rainbowcybercamguy dot com.

My grandpa Loren worked with you! When I was a kid, I got to visit the studio once. It was awesome to see the cameras operating off of binary coding. It was especially fascinating looking at the book artwork without any of the text on the pages. Thanks for posting your website!

Are this all serious. Reading Rainbow is coming back. Grew up with it.

I listen to his podcast, it’s especially wonderful while relaxing in a hot bath, no worries about dropping my e-book reader or my physical book. You can find it in many places and it is free:

https://www.levarburtonpodcast.com/

It should not be missed and for those with children, it can be played while traveling. My friends tell me it entertains their children and they rarely hear “Are we there yet?”

I read anything and everything that doesn’t go past me at a fast gallop and have since I was four. Levar is one of the greatest treasures of our world.

Thank you, Leah! I actually did not know this existed and I am also obsessed with LeVar. I also would have been concerned about it not being good and you have reassured me. This is number one on my movies to watch list now. Thanks!

Thanks for sharing this. Where can I watch it?

Thanks for this article Leah. I’ve admired LaVar Burton’s work as an actor for a long time but never saw Reading Rainbow – it launched while I was in college. Just recently I saw Mr. Burton as a guest on Finding Your Roots with Dr. Henry Louis Gates (Season 10, Episode 3). It includes a brief summary of Mr. Burton’s life story (believe it mentions the documentary). His thoughtful comments and emotions as Dr. Gates revealed information about his family tree made the episode memorable to me. Based on your review, I’m sure Butterfly in the Sky will provide further insight into this excellent man and the impacts Reading Rainbow had on children across America.

My little one loved that show. Whenever they saw an image of Burton, they’d excitedly call out “There’s Rainbow! There’s Rainbow!”

Loved your article. I did not watch as a kid as I was 17 when it premiered, but I did watch it with my kids . Mr. Burton not only taught us to love reading, but to read for one self and to others.